Historically, domestic violence research and awareness has focused on heterosexual relationships. However, recent findings show that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex (LGBTQI*) individuals experience domestic violence at equal or higher rates than their heterosexual counterparts.

A 2015 study on intimate partner violence (IPV) concluded that ‘there has been an invisibility of LGBTQI relationships in policy and practice responses and a lack of acknowledgment that intimate partner violence exists in these communities.’

Why does domestic violence in LGBTQI relationships seem to be an invisible issue?

The World Health Organization only declassified homosexuality as a mental disorder in 1990, so it’s unsurprising that research and policy change relating to LGBTQI populations is thin on the ground.

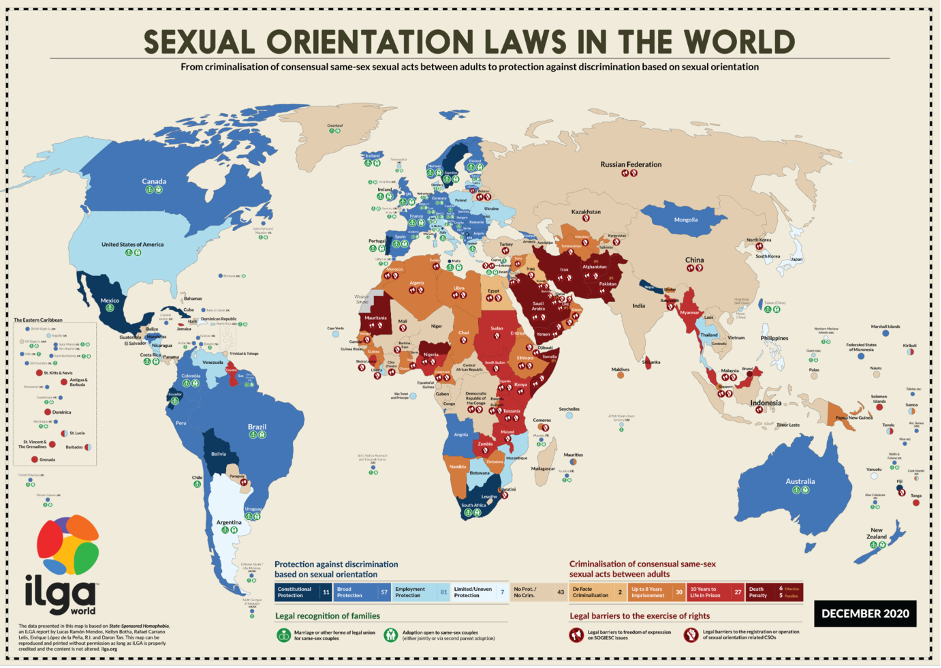

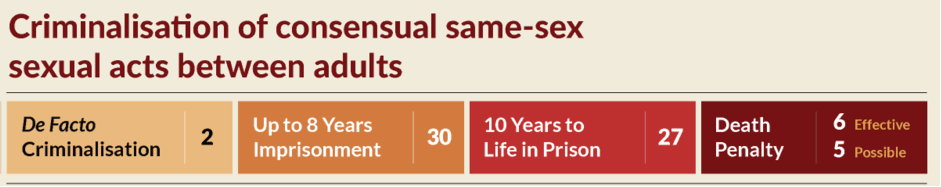

Violence against LGBTQI individuals isn’t just a problem in domestic spheres. Globally, people face inequality and violence every day, because of their gender identity and sexual orientation.

Did you know? Homosexuality is still illegal in over 70 countries.

Reluctance to report

LGBTQI domestic violence victims are less likely to report abuse due to ‘persisting homonegativity…in the justice system’. In other words, when you’re part of a system that doesn’t support your identity, you’re less likely to reach out for help.

Domestic abuse in LGBTQI communities can involve increased risks due to fears that individuals have about disclosing their sexuality or gender identity to others – especially in countries where being LGBTQI isn’t legal. Reasons that LGBTQI victims might not report domestic abuse include:

- The threat that people will ‘out’ them to family, friends, colleagues, or the wider community

- Prior bullying and hate crime earlier in life that may make LGBTQI people less likely to have confidence in support systems

- Societal beliefs that violence does not occur in LGBTQI relationships

- Lack of training and homophobia from service providers

Members of the global LGBTQI community may be denied assistance to domestic violence services as a result of homophobia, transphobia, and biphobia, where 45% of victims don’t report abuse, because they believe it won’t help them.

A varied global outlook

Although many countries are taking positive steps to implement change and address LGBTQI domestic violence, the approach is varied and uneven. There are even fewer initiatives that address transgender, intersex, and asexual-specific domestic violence.

In Russia, working to prevent and combat domestic violence is considered a ‘political activity’. That means chancing state harassment and intimidation if you speak up. In addition, Russian law does not recognise domestic violence as a stand-alone offence, meaning that the police can refuse to investigate or respond to complaints.

In Denmark, however, members of the police force were invited to participate in hate crime awareness training as part of a European Union-funded project. Alongside other national initiatives, the project fed into the development of a national hate crime toolkit and training manual for police officers. The toolkit includes police guidelines for handling LGBTQI violence.

Public awareness

Public awareness campaigns that address LGBTQI domestic violence are valuable foundations for change. A campaign in Brazil called, ‘Brazil Without Homophobia’, was launched in 2004 to raise awareness of LGBTQI discrimination.

In Thailand, the ‘School Rainbow’ campaign raised awareness of LGBTQI bullying and violence. Over 2,000 students and teachers drew rainbows around the grounds of schools to demonstrate that the spaces promote diversity and solidarity with LGBTQI communities.

Ensuring that the public is well-informed and has access to information can dispel myths surrounding LGBTQI violence, stereotypes, and gender roles.

Political solidarity

Messages of support and public engagement from political leaders can be particularly effective. Public officials and political leaders in the Bahamas, Belize, Cuba, and Myanmar have condemned violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation. These messages can put discrimination and violence in the spotlight and promote a zero-tolerance approach.

Although most political support doesn’t yet focus specifically on LGBTQI domestic violence, general condemnation of such discrimination has the potential to filter through and spark positive change.

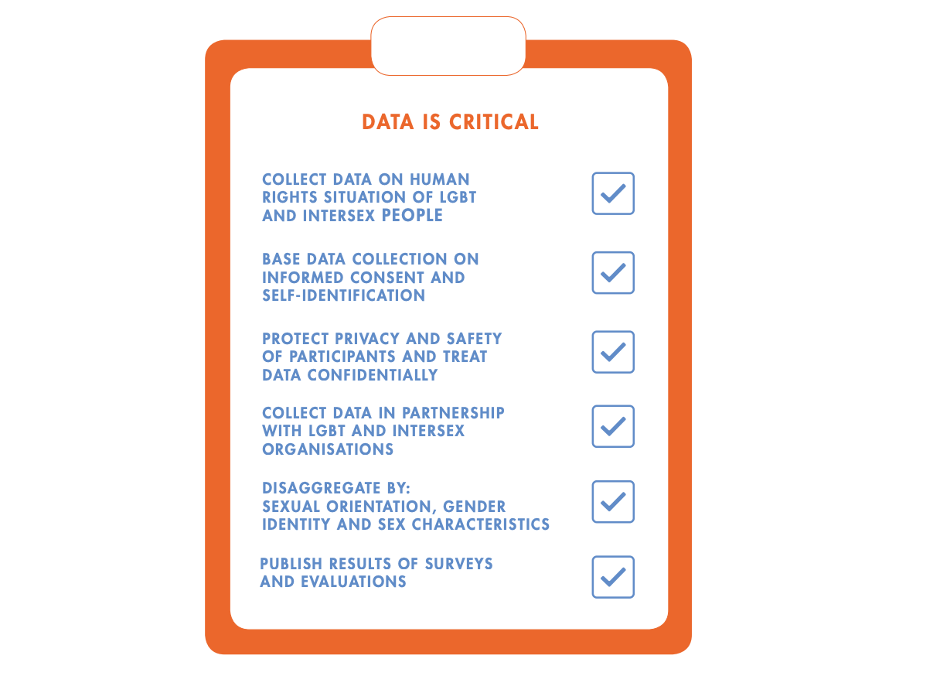

Data

The experiences of those who identify as LGBTQI are frequently missing from both data and mainstream depictions of domestic violence.

“States should place greater emphasis, in partnership with LGBT and intersex organizations, on monitoring the impact and effectiveness of measures being taken to combat violence and discrimination. This is particularly relevant in the context of ensuring that LGBT and intersex persons benefit and are included in efforts to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, which are centred around the commitment to ‘leave no one behind’.”

United Nations (2016). Living Free & Equal.

Towards visibility

With increased public awareness through community, local, national, and global initiatives, positive change is possible – especially when coupled with political solidarity and improved data collection.

Leave no one behind (LNOB) is a central part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It requires the combatting of discrimination and inequality to reverse unequal distributions of resources and create a thrivable future.

*THRIVE uses the LGBTQI acronym to refer to people who are from sexually or gender diverse communities and who may identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, trans, intersex, queer, questioning, or asexual.

References

Campo, M., & Tayton, S. (2015). Intimate partner violence in lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex, and queer communities. Retrieved from: https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/intimate-partner-violence-lgbtiq-communities

World Health Organization (2017). International Day against homophobia, transphobia, and biphobia. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/life-course/news/events/intl-day-against-homophobia/en/

Human Rights Watch (2013). LGBT rights. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/topic/lgbt-rights

Human Dignity Trust. Map of countries that criminalise LGBT people. Retrieved from: https://www.humandignitytrust.org/lgbt-the-law/map-of-criminalisation/

The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association (2020). State-sponsored homophobia. Retrieved from: https://ilga.org/maps-sexual-orientation-laws

Potoczniak, M., & Mourot, J. (2003). Legal and psychological perspectives on same-sex domestic violence: A multisystemic approach. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10689612_Legal_and_psychological_perspectives_on_same-sex_domestic_violence_A_multisystemic_approach

National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (2015). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and HIV-affected intimate partner violence. Retrieved from: https://avp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2015_ncavp_lgbtqipvreport.pdf).

Human Rights Watch (2018). Weak state response to domestic violence in Russia. Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/10/25/i-could-kill-you-and-no-one-would-stop-me/weak-state-response-domestic-violence

United Nations (2016). Living free and equal. Retrieved from: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/LivingFreeAndEqual.pdf