Diversity, in the way we use that word today, can refer to a wide range of things. In sports, diversity might mean having people with varying and complementary skills and backgrounds on your team. When it comes to institutional diversity, the concept cannot be applied simply on a macro level. It must also be applied on a grassroots level. Individuals are moulded by the different environments, families, surroundings, and cultures they grow up in. In addition to the individual conditions that create diversity, we also need to build social structures that promote it.

What is an Institution?

Through a sociological lens, some scholars think of institutions as objects (Ahmed, 2012). An object is usually made of something and by someone. Institutionalism has existed as an area of study in the social sciences for a long time. Its function has been the consideration of the role of institutions in our society (Ahmed, 2012). ‘New institutionalism’ is an emerging area of study in which scholars consider how institutions become instituted in the first place and entrenched over time (Ahmed, 2012).

It is enlightening to compare an ‘institution’ to an object, and to transfer the common properties of objects over to how we think about the institutions we participate in. For both objects and institutions there is a founding idea and a maker. Sarah Ahmed states that – “Institutions can be thought of as verbs as well as nouns: to put the “doing” back into the institution is to attend to how institutional realities became given, without assuming what is given by this given.” (Ahmed, 2012).

The institutions we live alongside every day are often taken for granted. Their histories, foundations and roles are assumed or left uninterrogated. However, institutions are ultimately also a phenomenon. This means that they appear and are continually made and remade by their routines. Thinking of institution as a verb, institutions are ‘done’; they are acted. There is a routine or a regular feature to institutionalism that is normalised, including the element of ‘diversity’.

Most consider diversity from a certain taught perspective. Because many people have been educated in the same vision of diversity, diversity as a concept is institutionalised and operative in a certain way within us. Following Ahmed – “We could even say that diversity workers live an institutional life.” (Ahmed, 2012). Many people live two types of parallel lives – their individual personal lives and their institutional lives. If we are living our institutional lives at work, and are simply following and acting out the often unquestioned imperatives of an institution, can we really say that our institutions are diverse?

Race, social status, age, sexuality, disability, and cultural background have been discussed from many perspectives and the need to draw from the skills of people from all of these groups has now been institutionalised – this is what we call ‘diversity’. Following ‘new institutionalism’, we must ask – what was the need for institutionalised diversity in the first place, and how exactly was it institutionalised? How do we really make our institutions diverse instead of masking the current realities of our institutions?

institutional diversity and inclusion

Homogeneity through whiteness

When discussing diversity in general today, there is a strong association between race and creating diversity. Ahmed draws attention to how whiteness plays out in our institutions, despite attempts to hide it.

“When our team was their picture, it created the impression that the organization was diverse. Arguably this was a false impression: the other teams were predominantly white.”

Ahmed, 2012

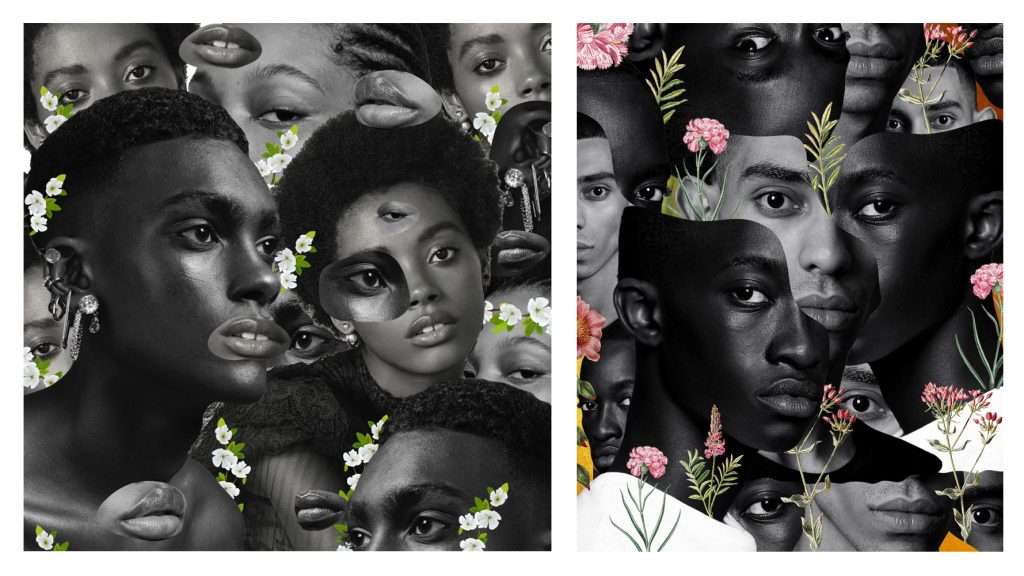

Often, institutions leverage the racial backgrounds of their teams in order to appear progressive and diverse. Despite appearances, when you consider an institution as whole, at least in western societies, they are predominantly white. Institutions mask the whiteness of their workforces by using images of diverse people (and other techniques) to appear colour-blind.

Commitment or colour-blindness?

“Colorblind ideology aims to treat individuals as equally as possible, without regard to race… However, colorblindness alone is not sufficient to heal racial wounds on a national or personal level. It is only a half-measure that in the end operates as a form of racism.”

Williams, 2011

Colour-blindness can effectively be considered a belief that social exclusion, systematic racism, and social injustice do not actually take place in society. Institutions moving towards diversity and equality must demonstrate a certain commitment to upholding these ideals. There needs to be constant open communication between different departments of an institution. Otherwise, the reality of an institution will slowly revert to its traditional and comfortable, meaning ‘white’ state.

As Ahmed states, many institutions make diversity commitments that they cannot or do not keep. Ahmed questions if institutions commit to diversity initiatives out of pressure to comply to the law, or if diversity is really a true value of that institution (2012). There is a risk that whiteness and ‘colour-blindness’ will contribute more to homogenising our institutions, rather than increasing their diversity and inclusivity.

Post-racial thinking

The European Union (EU) and most countries in Europe operate as if they moved to a form of post-racial thinking. According to Sayyid (2017), this presents a major problem as anti-racism has never been adequately discussed at a deep social and cultural level. Europe has bypassed its need to reckon with its racist past, opting instead to move to post-racial thinking. This avoids the core need to tackle racism through the lens of anti-racism. The recent events of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in the United States and other similar events in other countries has shown that racism still exists in the West.

According to Sayyid (2017), the concept of the post-racial state first emerged in the United States during the election and inauguration of Barack Obama. There was a belief that America had triumphed over its racist past.

The broad historical arc of racial thinking and institutionalization marks all of modernity. From the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries, slavery framed much if not all the thinking concerning race. Slavery was fuelled by ideas of inherent inferiority and superiority, and reinforced them. Racial ideas have always been diverse, shifting over time, even throughout slavery.

Goldberg, 2015

Post-race thinking, on paper, considers that there are no disparities between races. Even if in, for example, the United States there have been significant historical racial disparities towards blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans. These groups have remained socially disadvantaged in almost all indexes of well-being compared to the white population (Goldberg, 2015).

Paradoxes in the Post-racial Mindset

The post-racial mindset is full of paradoxes and contradictions that threaten true social and institutional diversity. The first telling sign is that despite attempts to declare a post-racial state, social tensions around race have only increased. After Barack Obama became president things only escalated further. Despite the popularity and success of the first black president of the US, there has been an increase in media coverage of police violence against black people, and a resurgence of anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, and anti-immigration sentiment in Europe (Goldberg, 2015). This trend maps clearly onto the rise of populism around the world. Post-racial thinking has done nothing to interrupt the continuation of racism and racial tension.

Social media influences many people around the world, and many now use it as their primary source of news (Shearer & Mitchell, 2021). One major issue with social media use is misinformation and vulnerability to bad actors. For example, in Myanmar, Facebook was widely used by nationalists to incite violence. L:ater Facebook was criticized for being slow to remove inappropriate content (Lee, 2019). Depending on context, often xenophobia is fuelled and inflamed by the use of social media.

Immigration policy has become one of the biggest points of tension in Europe in the past decade (European Commission, 2017). The way political parties lead these discussions has created massive political polarisation. Ultimately, it is not difficult to create outrage in a country’s white population – you just need to emphasise the threat that cheap labour or talent from abroad poses to employment stability (EconPol, 2020).

According to Goldberg another paradox of the post-racial mindset is its suspicious convenience in regards to white privilege. Bluntly, post-racial thinking masks the effects of white privilege (2015). Post-racial thinking has created a blinded perspective of racism, making it even harder to address real grievances.

bell hooks discusses the social imagination that the historical fact of slavery has created in black households. She argues that collective trauma plays a role in creating domestic violence in black communities (2015). Slavery has a lasting social residue that continues to ripple out and affect the lives of current living people. The social imaginary that discourses surrounding the history of slavery in America has created disempowers black people.

In the time that has passed between when slavery was abolished in the US and now, this social imagination has not allowed us to understand the psychological trauma that persists intergenerationally or to heal it. White privilege plays a role in maintaining the oppressive conditioning of this social imaginary. For example, bell hooks points out that slaves must have repressed their emotions to survive (hooks, 2015). Due to the risk of lynching or other social punishments for racial transgressions, this type of conditioning continued all the way up until the end of Jim Crow. This mindset is a collective trauma that remains hard to clear.

Post-racial thinking masks the realities and especially the subtleties of historical and contemporary racism, masking its own paradoxes.

Multiculturalism

Goldberg argues that the ‘post’ in ‘post-racial is the epitome of the rejection of multiculturalism. Post-racial thinking is a modern stand-in for multiculturalism, and at the same time homogenises instead of diversifies (2015). This is of note when considering how to achieve true institutional diversity and inclusion, given that many of our institutions are tempted to think post-racially.

A major part of multiculturalism is a set of ideals called racial liberalism, mostly posed as a response to white hegemony. However, these policies have largely failed and this has given way to an expanding neoliberal post-racial mindset. Post-racial thinking is a response to the seeming difficulty of multiculturalism, according to Goldberg (2015). Due to a resurgence of neoliberalism, which emphasises individual self-responsibility and limits self-actualisation to capitalist modes, the political promise of multiculturalism has been greatly diminished. According to Goldberg – “This goes hand in glove with the rising stress on post-racial individualization and the renewed emphasis on nationalist discourses”(Goldberg, 2015).

Heterogenous belief

Globalisation, which has increased population migrations and movements globally, has led to cultural heterogeneity in many countries. This could be considered a positive outcome for social and cultural diversity and inclusivity around the globe. Immigration is driving cultural diversification. However, there have been increased tensions about borders (Goldberg, 2015).

After immigrants begin integrating into a country after settlement, due to national institutional standards and processes they often end up limited and constrained. This is a recipe for racial alienation (2015; Weiner, 2017). When it comes to immigration policy, post-racial thinking is dispassionate and cold, and limits the participation of those who are outside the majority. In this way, our institution often prevent us from enjoying the full benefits of an increasingly heterogenous culture and create social inequality. Heterogeneity is a principle that can help us achieve true institutional diversity and cultural wellbeing.

Can Deep equality achieve real institutional diversity and inclusion?

“Deep equality is not a legal, policy or social prescription, nor is it achievable by a magic formula that can be enshrined in human rights codes. It is, rather, a process, enacted and owned by so-called ordinary people in everyday life. Deep equality is a vision of equality that transcends law, politics, and social policy, and that relocates equality as a process rather than a definition, and as lived rather than prescribed.”

Beaman, 2014

Deep equality in its core, as Beaman states, is not a legal term but rather a philosophical belief. One of its core tenets is a focus on performing gestures of equanimity in our “day-to-day interactions” (Beaman, 2014). Beaman believes that deep equality “recurs, circulates, reshapes and reframes and thus forms part of the bedrock of social life” (2014). Deep equality requires the reshaping of our own social imaginaries. It can and should then be embedded through in our institutions to create institutional diversity and inclusion.

Conclusion

When diversity and equality aren’t present in our institutions, groups of disadvantaged people are excluded. Social inclusion is vital to the wellbeing and development of all people, particularly young people. There are many scholars and policy-makers who are asking essential questions surrounding diversity and equality. Some may come from diverse backgrounds and use their lived experience to inform their work, and so have first-hand experience of the dynamics of social inclusion and exclusion.

Difference comes with the risk of being excluded. There are many reasons an individual might lose their trust in the society in which they live. Real commitment to institutional diversity is needed to avoid the systemic exclusion of people who would otherwise contribute to the strength of that institution.

Healing inner wounds creates a stronger possibility of reconciliation (hooks, 2015). Through reconciliation, there is a possibility to “restore to harmony that which has been broken, severed, and disrupted.” (hooks, 2015).

To learn more about how The THRIVE Project is researching, educating and advocating for a future beyond sustainability, visit our website. You can follow our informative blog and podcast series, as well as find out about our regular live webinars featuring expert guests in the field. Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates.