Community sustainability initiatives are local policies that take into account multiple human needs. A sustainable community is a place where people of diverse backgrounds and perspectives feel welcome and safe, where every group participates in decision-making, and where prosperity is shared. Therefore, initiatives for a sustainable community are those that address the goal of ‘Social Sustainability’ (SS), and serve the overarching goal of sustainability for our planet.

However, there is no definitive statement as to what the terms Sustainable Community or Social Sustainability mean. Neither the United Nations (UN) nor any other institution, has so far developed a comprehensive description. Furthermore, the goals lack high-quality agreed indicators of progress, which are crucial for monitoring success.

So, how do we create useful community sustainability initiatives? For example, how do we know if social policies like ‘Social Mixing’ actually provide effective solutions? Or, does the integration of different socio-economic groups actually lead to worsening inequality?

Evidence shows that social, economic, and environmental planning are essential to good urban development. Failing to address these issues leads to unsustainable outcomes. It is true, for instance, that a lack of affordable housing leads to greater social instability.

By contrast, good planning and strong community sustainability will produce resource-efficient, stable, and cohesive societies.

In this article we look more closely at what ‘community sustainability initiatives’ might mean in terms of policy, and how ‘social sustainability’ may be achieved in practice.

What Is Social Sustainability (SS)?

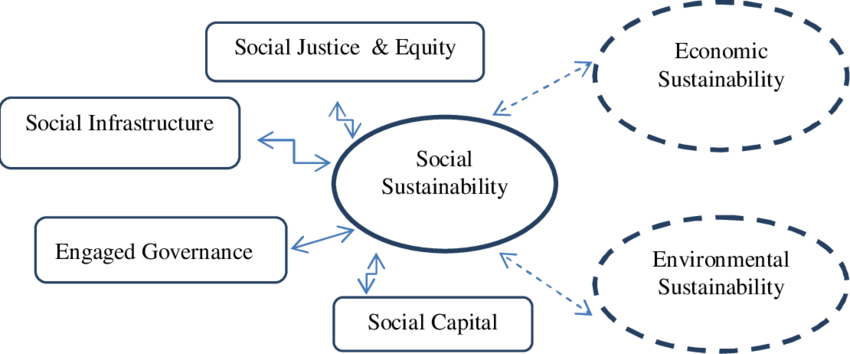

Social Sustainability (SS) means those aspects of sustainability that relate to people. In the 1980s, SS became a popular term in the field of ‘Sustainable Development’. Sustainable Development referred to the principle of being able to supply the material needs of consumers, whilst also maintaining the integrity of the environment (Bridger and Luloff, 2022). Sustainable Development would ‘meet the needs of the present without compromising future generation’s ability to meet their needs’ (WCED, 1987; Winston, 2021). Social Sustainability is achieved by creating positive outcomes for both people and the planet. And, in many cases, these outcomes are interconnected.

However, the idea could be used in almost any context without the application of any legal or conceptual rigour. So, policymakers at the time did not consider it necessary to explore the concept in detail. Nevertheless, there has been renewed interest in Social Sustainability since the 1990s (Bridger and Luloff, 2022; Winston, 2021). There is now a great deal of literature on the sustainable community as a key pillar of Sustainable Development.

Cornerstones of The Sustainable Community

The four cornerstones of the sustainable community have been defined as ‘equity, awareness for sustainability, social participation, and social cohesion’ (Winston, 2021). The key point seems to be that there is a link between meeting a community’s basic material needs and an increased willingness of its members to be socially inclusive. Also, meeting basic needs helps to keep demand within sustainable limits.

“First, basic human needs must be addressed…to ensure people can participate in society. Ensuring ‘sufficiency’ in meeting needs is crucial as this helps to ensure the provision of welfare within planetary boundaries.”

– Nessa Winston, 2021

In turn, communities are able to address environmental issues more effectively. For example, people learning about their carbon footprint to improve their own wellbeing has provided useful educational outcomes on environmental issues (Winston, 2021).

Community sustainability initiatives through social mixing

However, in urban planning and social housing, ‘social mixing’ is an initiative that has attracted some controversy. The idea is to promote socially diverse and mixed neighborhoods. It stems from a belief that communities become more ‘positive’ through social mixing between diverse groups (Walks, 2015; Arthurson et al., 2015; Mereine-Berki et al., 2021). Greater mixing is thought to improve cultural and economic outcomes. Further, ethnic, and class-based diversity is believed to yield greater social unity, greater connections, and decreased inequalities (Mereine-Berki et al., 2021).

By contrast, negative outcomes are often associated with the geographical segregation of poorer communities from the rest of society.

Or is it Just a Polite Term for Gentrification?

Critics argue that social mixing could, in some scenarios, actually be harmful. Their main criticism is that social mixing is simply a euphemism for gentrification, in which people living in poorer neighbourhoods are displaced by wealthier families.

Furthermore, in socio-economic studies, impoverished urban environments are rarely tracked (Mereine-Berki et al., 2021). This is especially true in societies where the creation of economic capital is seen as the primary goal.

In addition, some social researchers argue that inequality is poorly measured in ‘socially mixed’ neighborhoods. Social divisions between advantaged and disadvantaged groups are disguised by the dominant activities and social behaviours of its wealthier members (Meij et al., 2021).

The UN’s Vision For Social Sustainability

Interestingly, the UN’s first sustainability goal is the eradication of all forms of poverty (SDG 1). Social Sustainability is seen as a critical priority for our planet. In fact, the UN’s five P’s or ‘indicators’ of the 2030 Agenda have a strong focus on people. They are:

- An end to hunger and poverty so that people may prosper;

- Protecting the planet from degradation, now and into the future;

- Creating prosperity for people, so that they can live comfortable lives;

- Ensuring peace, to end fear and violence in society, and

- Creating meaningful partnerships between all levels of society.

The Problem with Broad Based Goals

However, many social researchers believe that the complex reality of poverty and inequality is actually being obscured by their reduction to single normative statements like SDG9 or SDG11 (Parechi et al., 2022).

For example, the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 11.1 aims to “ensure access for all to adequate, safe, and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums” by 2030. Yet, due to price and rental increases, many communities are still struggling in 2022, especially in poorer neighbourhoods.

That said, SDG 11.1 proposes a number of specific indicators of success. These include:

- the percentage of the population covered by national social protection programs

- the number of consultations with a licensed health facility in a community per person, per year

- the percentage of the population using safely managed water services

- the percentage of the population using safely managed sanitation services

- the share of the population using modern cooking solutions.

community sustainability initiatives For a thrivable community

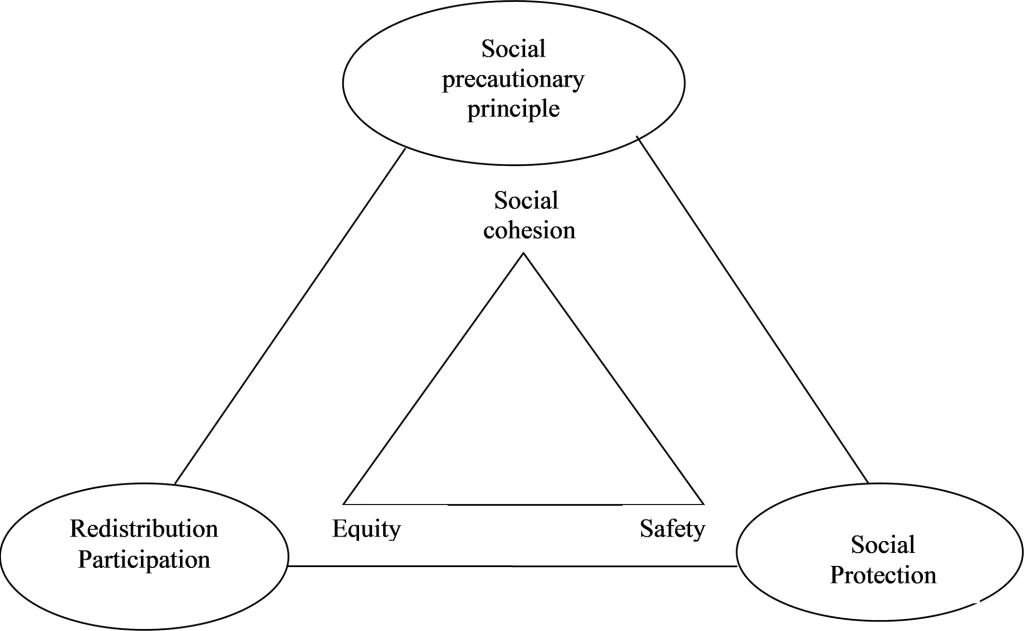

Instead, Ballet, Bazin, and Mahieu provide a more sophisticated discussion about the ‘social pillar’. The social pillar is presented as one of the three foundations of sustainability, alongside the ‘environmental’ and ‘economic’ pillars. It is conceived as a triangular framework embracing the key elements of social cohesion, equity, and safety (see Fig 1 above). Neglect of the social pillar, by focusing too heavily on the environmental and economic aspects of sustainability, creates poor public policy.

‘Social cohesion‘ represents a coherence in the behaviours and attitudes of a society. ‘Equity‘ represents both ‘distributive’ and ‘procedural’ justice because adequate participation in society by all is vital to its success. ‘Safety‘ involves protection, specifically from economic shocks, but also in terms of a society’s overall resilience to threats.

“The three criteria we propose are bound together. We would consider that they are the core of the social pillar, and that they require the implementation of policies which are not usually associated with environmental issues. This provides a whole new perspective on sustainability.”

Ballet et al, A policy framework for social sustainability: Social cohesion, equity and safety.

Community Sustainability Initiatives as Public Policy

The ‘outer triangle’ in the diagram above represents the policy approaches that support social cohesion, equity, and safety. In the first instance, we must develop policy approaches that avoid the deterioration of Social Cohesion. For example, building an irrigation system might benefit one sector (say, farmers) but create poverty in others (the fishing community).

Therefore, ‘social precautionary policy’ means considering the potential effects of economic and environmental policy on social cohesion.

Equity, in turn, requires policy that actively redistributes wealth and thereby encourages greater participation in decision-making. This is a high priority in societies where a large disparity in wealth exists because there is seen to be a strong connection between social and environmental inequity.

Finally, the element of Safety requires policy that prevents ‘shocks’, specifically the impact of economic shocks on a society. The close relationship between poverty and environmental degradation makes measures to prevent poverty vital. So, effective social protection policy requires programmes that address the risks of economic crises. They must also address vulnerability to disasters as economic crises can be caused by extreme weather events.

A ‘Thrivable’ Framework for Social Sustainability

If we can achieve greater social cohesion, equity, and safety, we help to build social sustainability. This makes environmental and economic sustainability more achievable. So, an analysis of the social pillar provides a useful blueprint for practical Community Sustainability Initiatives. Actions like these can help to guide public policy. They can also inform the practice of individuals and families.

For example, consultation with and listening to the lived experience of the more marginalized is one way to become aware of threats to the ‘social pillar’ in your community or city.

Thrivability

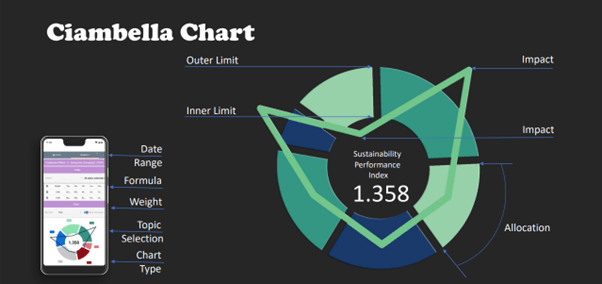

The THRIVE Framework examines issues and assesses potential solutions in relation to the goal of ‘thrivability‘. Thrivability is a concept to describe a state in which humanity is not only able to survive into the future, but thrives. Thus, thrivability is the next step, a state ‘beyond sustainability’.

The THRIVE Framework recognises that human happiness can sometimes compete with environmental wellbeing, which is why we use our Ciambella Chart (below) to illustrate the ‘thrivable zone’. This is the area between the ‘social floor’ (the minimum required for people to live happy lives) and an environmental ceiling (the maximum damage that we can do to the environment before it becomes unsustainable).

Overlaid on these thrivable zones are visual measurements that show the impact of particular activities – whether something is inside the thrivable zone – or where it falls short. In this way we can measure the effectiveness of sustainability measures with predictive analyses made possible by modern technology.

Conclusion

At its core, sustainability means simply being able to continue, to survive. THRIVE believes that humanity can do much more than that with existing, and emerging, technologies like Big Data and AI. We believe it is possible for people and nature not only to co-exist, but to live in harmony and solidarity.

To learn more about the purpose of The Thrive Project and The THRIVE Framework, visit our website and sign up for our newsletter. Thrive also produces live webinars on sustainability subjects featuring expert guests and the Thrive community. You can also catch our regular podcast series and blog posts.

GOT A QUESTION ON THIS TOPIC?