Global population growth rates affect every element of collective human well-being, from the management of resources, to urban population density, to our ability to feed the planet.

Religion, economics and differences in social structures all influence a country’s birth rate. Further, there is a strong link between birth rates and countries suffering from hunger and malnutrition. Therefore, to improve human wellbeing, we must consider how decisions about childbirth are made.

This article looks at the rapid population growth that took place after World War II and explores the relationship between population growth rates, economic growth and sustainability. We also examine related questions like ‘what causes changes in population growth rates’, and ‘how do population trends emerge over time?’

Finally, we discuss the enormous challenge facing global organisations like the United Nations over the coming decades, as they seek to address important issues of hunger and inequality amidst a growing world population.

Histories of rapid population growth

In the period following WWII, the global baby boom was most pronounced in the developed countries. This led to a rapid increase in their populations. For example, the United States’ strong post-war economy led to a rise in birth rates, assisted by advances in antibiotics and early childhood health (Kopnina & Washington, 2015).

Whilst US fertility rates have steadily declined in the decades following WWII, fertility rates in developing countries remain high. This is due to a number of factors, including lack of access to contraception. However, social structures, religious beliefs, economic prosperity, and urbanisation all play a part. Birth rates and abortion rates for every country are influenced by such factors (Nargund, 2009). Now, with the economies of some major developing countries growing, birth rates are very likely to increase again. Therefore, we must prepare for a major increase in global population growth rates in the near future.

Population Growth Rates from 1950-2100

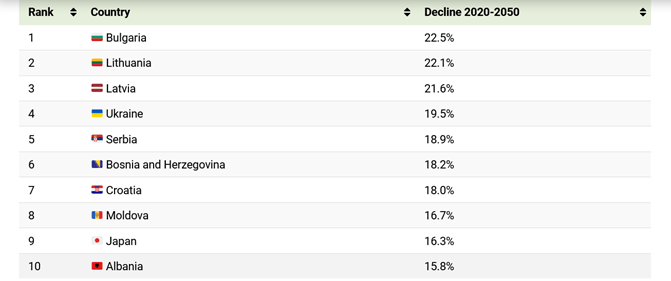

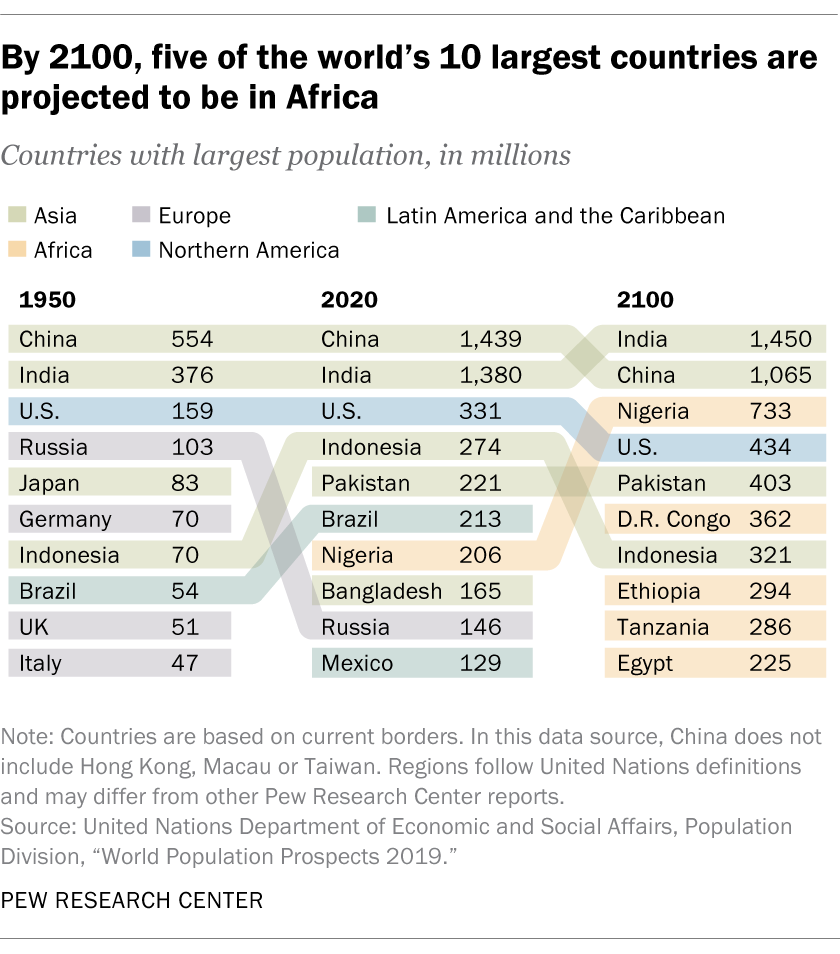

The PEW Research Center provides excellent data on population growth by country between 1950-2100. They also provide an excellent method of analysis which shows how population growth rates have changed, and will continue to change, over time. From a quick glance at this table, we can tell that, although China is still the country with the largest population, it is projected to be surpassed by India by 2100 (Gramlich, 2019). Also of note is the developed countries that experienced high birth rates during the baby boom which are now no longer among the 10 most populous countries in the world (except the U.S.). Moreover, by 2100, the 10 most populous countries will all likely be in Africa. This is due to improved standards of living expected to accompany economic growth (Gramlich, 2019).

What affects Birth Rates?

Religion and population growth rates

Religious belief is a major factor in population growth. Between 1950 and 2020, the number of children in the world has doubled globally. So, what did religion have to do with this?

Families of Islamic or other Eastern faith living in Asia used to have 6-7 babies each. Many tended to have a low income, but this did not affect their decision to have babies.

In countries where the majority practice Islam and Christianity, and where people typically live on low incomes, families have tended to have more children. A major factor is the higher incidence of child mortality rates in those countries.

By contrast, the prevailing belief in Western Christian societies has been that a family needed significant income before having children. If anything, that attitude has only become more prevalent over time.

By 2010, the typical family in around 80% of all countries had 2 children on average. Birth rates are slowing in many developed countries. However, the data is telling a very different story to 1960, according to Hans Rosling, and population growth rates vary between countries in response to a range of factors. Nevertheless, the world population continues to grow.

Notably, there appears to be a correlation between the renunciation of religion and a declining population. In countries with faster population growth, census data reports fewer numbers of atheists and agnostics.

Economic growth and population growth rates

Historically speaking, economic growth leads to population growth. However, increases in the standard of living can also cause populations to decrease. This is because people will tend to become more career oriented as their economy grows. They are also more likely to have access to contraceptives and higher levels of education, both of which invite greater individual choice (Nargund, 2009).

Interestingly, research indicates ‘a clear correlation between poverty and religiosity’, according to Our World in Data. So, a person’s religious beliefs may be keeping them poor, and poverty, in turn, may be encouraging people to be more religious. Thus, birth rates in certain countries might suffer from a sort of static predictability. This assertion is explained in the YouTube video, below.

How Social Structures affect Hunger During Population Growth

“A country’s ability to feed itself very much depends on three factors: availability of arable land, accessible water, and population pressures. The more people there are, especially in poor countries with limited amounts of land and water, the fewer resources there are to meet basic needs. Development stalls and economies begin to unravel if basic needs cannot be met. In some poor countries, attempts to increase food production and consumption are undermined by rapid population growth; migration from rural to urban areas; unequal land distribution; shrinking landholdings; deepening rural poverty; and widespread land degradation. Lower birth rates, along with better management of land and water resources, are necessary to avert chronic food shortages.”

Sadik, 1991

Sadly, not much has changed since this quote from 1991. Globally, we produce enough food to feed everyone. However, the food we produce does not reach all of those who need it.

Science and Technology have improved food production. Yet, the poor use of land, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides, has meant it has come at a significant environmental cost. Consequently, there is now an urgent need to create sustainable food production methods, as well as a means of distribution capable of feeding everyone (Sadik, 1991).

To tackle inequalities in the food supply we must understand how it is rooted in a power structure. Generally, groups that are already socially excluded from social, economic, or political power suffer most from hunger and malnutrition during periods of famine.

Famine in Yemen

The situation in Yemen is a text-book case study of the interconnection between hunger and poverty in times of resource scarcity. A brutal war has led to rising hunger and food insecurity. Despite ongoing humanitarian assistance, 17.4 million Yemenis are food insecure. That number is estimated to reach 19 million by December, 2022.

Elon Musk on population collapse

Prominent tech billionaire Elon Musk has commented several times on population growth rates. At first, Musk argued that high global population growth rates would destroy the earth. Now, he says that population decline is cause for concern, because it is leading the world towards a population collapse.

Whatever his position, it is hard not to see Musk’s comments in light of his ambition for colonising Mars. He says, “if there aren’t enough people on Earth, then there definitely won’t be enough for Mars”.

Nevertheless, colonising Mars is a much lower priority for those who argue the sustainability of our existing biosphere is number one. For many scientists, inhabiting Mars is not only a suspect, but pointless, endeavour. If we cannot secure the future of Earth, what value is Mars?

So, what does ‘population collapse’ actually mean? Simply stated, it means there won’t be enough people for the world to function in the future. The global fertility rate was 2.5 in 2020. That rate is predicted to drop to just 1.9 by 2100. With the global average number of childbirths dropping, the fear is that earth will not have enough people to sustain human civilisation.

Musk’s fears about population collapse were debunked by a number of experts. Still, such views remain very influential, regardless of proof. Casual observations like these can be reckless, especially as they often generate misinformation online. With the pressing issues of environmental collapse and species extinction, uninformed opinion can be extremely harmful.

Population Decline in Rich Nations

Behind the current growth in global population, there is increasing demographic diversity. Whilst some of the world’s poorest countries are concerned with meeting the needs of a growing population, rich nations are worried about how to promote fertility.

Over the last 50 years, fertility rates in developed countries have dropped drastically. In 1952, the average family had five children—now, they have less than three. Statistically, countries need at least two children per couple (a rate of 2.1 rate) to sustain their population without migration.

Famine, war, environmental disaster, and infectious disease were some of the main reasons populations declined in the past. Today, however, low fertility rates are one of the main drivers. Before considering the consequences of population decline, let’s delve a little deeper into its causes.

Education and family planning

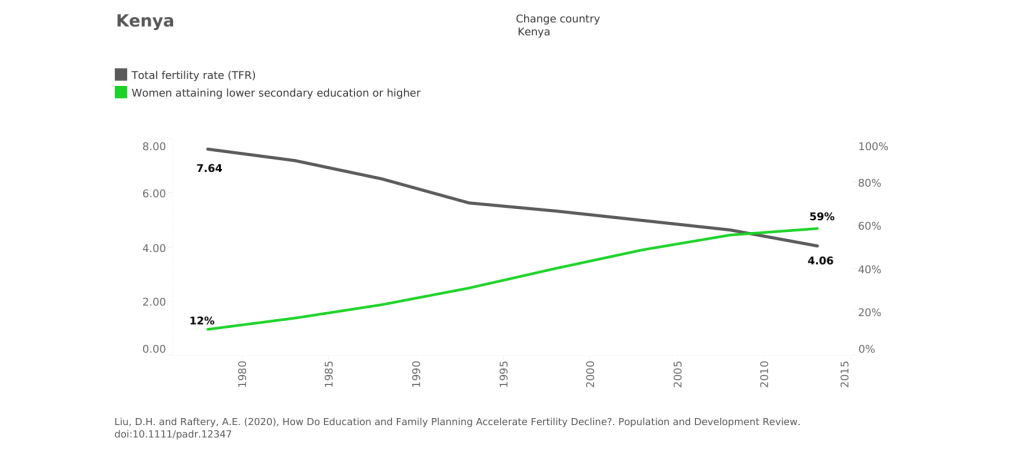

A study conducted by the University of Washington identified important factors in fertility rates. These include the number of years girls attend school, and the overall enrolment numbers for children. The educational attainment of girls in their early teens is particularly relevant (Liu and Raftery, 2020).

The above figure illustrates that women who attain secondary education or higher in Kenya are more likely to bear fewer children. Thus, higher education may contribute to a decline in fertility. The conclusion is that education delays a woman’s entrance into her reproductive life by increasing the age at which they will get married. Further, having fewer children and entering into marriage later generally means that their children are less likely to go hungry. Basically, more resources are allocated per child, so health and survival rates are better overall for both mother and children.

Notwithstanding, the availability of birth control and family planning services are also having an enormous impact. Even women without formal education are having fewer children than they did in previous decades.

The Matlab maternal and child health family planning program showed some of the earliest evidence that access to family planning leads to increased contraceptive use and reduced fertility. The program was introduced in 1997 in the Matlab sub-district of Bangladesh, a low-income rural setting. As a result, the Total Fertility Rate declined in Bangladesh from 6.9 in 1970 to 2.0 in 2019.

Economic uncertainty

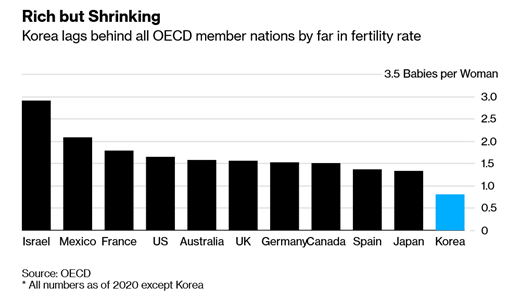

In August 2022, South Korea broke its own record for the world’s lowest fertility rate. According to the South Korean government, the rate of childbirth dropped from 1 child per woman in 2018 to 0.81 in 2022. Also, South Korea recorded more deaths than births for the first time in 2020.

Economic pressures, career factors, high costs of living, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic are still discouraging Korean couples from having children. As a result, South Korea is the fastest ageing country among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations.

Birth control

Strict policies have been enforced in some countries to control population growth rates. China’s one-child policy, for example, was designed to curb that country’s explosive population growth in the late 1970s. However, one result was a significant and disproportionate ratio of males to females in China driven by sex-selective abortions and infanticide. Subsequently, the Chinese government has relaxed the policy. However, the expected increase in fertility rate has not yet materialised.

Environmental concerns and resource depletion

The antinatalist movement advocates for couples to put off having children because of concerns about the environment. However, there is still ongoing debate on whether choosing not to have children would have any significant impact. Emissions per person vary considerably between countries, so disparities in their carbon footprint are more likely to be due to available technologies and behaviours.

Nevertheless, global population growth rates and the consumption habits of rich countries do put enormous pressure on biodiversity and the Earth’s resources. They also exacerbate food and water shortages, and reduce resilience to the effects of climate change.

Moreover, population pressures make it harder for vulnerable groups in less developed countries to rise out of intergenerational poverty.

The choice to not have children

The idea that having children is environmentally irresponsible seems to be gaining traction, especially in developed nations. Denmark, for example, is struggling to keep their population at 5.6 million. The biggest cause of the country’s declining population is young couples consciously choosing not to have babies. One Danish travel agency, “Spies Rejser”, is even urging young couples to go on vacation, where the chances of conceiving are statistically higher.

The Consequences of a declining population

A rapidly ageing population is likely to offset any benefits to the earth from lower birth rates. Low birth rates lead to:

- undermined economic growth

- a shrinking workforce and more labour automation

- fewer consumers

- a rapidly ageing population in need of care

So, the outcomes of population growth rates and the impacts of population decline are not straightforward. There are no easy answers for a world population about to hit 9 billion. However, a number of research organisations are turning their attention to ‘complex wicked problems‘ like these. The THRIVE Project, for example, is developing a framework designed to measure the impact of particular actions on vastly complex and interconnected phenomena relating to sustainability. As such, sophisticated, technology-driven analysis is vital to addressing the sheer volume and variety of data now available on environmental and societal issues.

For example, even if fertility rates continue to decline over the next few decades, the sheer numbers of people having babies will maintain the current momentum. A large cohort of young people will enter their reproductive years in the coming decades and this will have a major impact on population growth. The world population is set to hit 9.8 billion in 2050, according to the UN. It will hit 11.2 billion by the end of the century.

How are we going to feed a Growing population?

Consequently, population growth rates could exacerbate food and water shortages. By some estimates, the planet can conceivably produce just enough food for 10 billion people. Nevertheless, around 11 per cent of people worldwide are currently going hungry. 98% of those are in developing countries. Therefore, changing how food is distributed has become the most critical issue.

Some ways to ensure the supply of food for a growing population include:

- Sustainable food production systems

- Protecting forests and land

- Fully utilizing available land for agriculture

- Using smart farming technologies

- Changing our diet by reducing our meat consumption

- reducing food waste and overconsumption

The agriculture sector, in particular, can become more productive by adopting efficient business models and strengthening stakeholder partnerships. They also become more sustainable by directly addressing greenhouse gas emissions, water use, and waste disposal.

Conclusion

By simply reducing population growth we will not solve hunger and malnutrition. Holistic solutions that support economies, families, and the environment are more practical options. Therefore, we must look at all aspects of our food production and find effective ways to deliver food security to current and future generations.

Advocating for coercive population control is likely to encounter significant resistance, and it may even be counterproductive. Instead, implementing sustainable solutions using knowledge and technology that already exists will go a long way towards protecting our planet’s finite resources and human wellbeing.

THRIVE is a not-for-profit, for-impact organisation dedicated to researching, educating and advocating for sustainability. Our mission is the maintenance and improvement of quality of life for all, and a flourishing, or ‘thrivable‘, future for the Earth.

To learn more about how The THRIVE Project, visit our website. You can follow our informative blog and podcast series, as well as find out about our regular live webinars featuring expert guests in the field of sustainability. Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates.

GOT A QUESTION ON THIS TOPIC?