COVID-19 became officially a pandemic on the 11th of March 2020. Nobody then could have guessed its long-term socio-economic impacts. Like all global disasters, the pandemic hurt low income and vulnerable communities the most. Let’s explore the link between poverty and the pandemic.

Globally, the virus has been deadlier and more transmissible among low-income communities. It also increased poverty rates and created a foundation for continued economic depression.

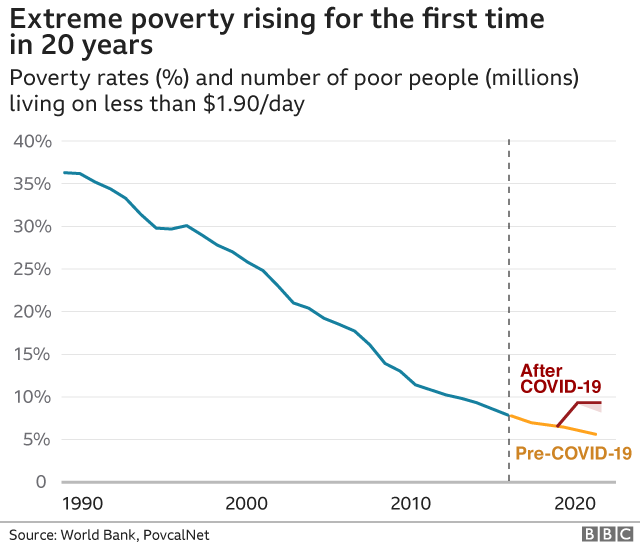

In 2020, the World Bank estimated that an extra 88 to 115 million people would fall into extreme poverty.

What is the link between poverty rate and the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic?

The pandemic has reinforced pre-existing socio-economic problems present within lower income communities. The most common of these relate to unemployment, poor access to nutrition and health care, as well as higher rates of chronic diseases and mental illnesses.

Global health guidelines recommend preventative measures to contain the spread of the virus. Unfortunately, this luxury remains out of reach for the disadvantaged. Without financial safety nets, people need to keep working to survive.

Unlike wealthy countries, many lower income countries are unable to fund social safety nets. This leaves them further unable to combat Covid-19’s economic fallout. Even countries with viable safety net programs leave vulnerable communities unequally affected. Large scale studies conducted in Australia, the US, and the UK revealed higher risk of COVID related complications in lower income and ethnically diverse neighbourhoods.

5 ways poverty affects the spread of the virus:

- Low wage workers have jobs that do not allow them to work from home. These are more often essential service jobs.

- Low-income areas are more likely to be overcrowded. This makes social distancing difficult, if not impossible.

- People who earn less are more likely to use public transport.

- People with lower incomes have limited access to healthcare services.

- Pre-existing health conditions (such as diabetes, heart, and lung disease) are common in those living in low-income areas, which may cause higher infection and death rates.

Unemployment and Covid-19 around the world

The Philippines

This Asian nation suffered one of the world’s longest lockdowns with strict stay at home instructions. Many criticise these restrictions as highly militarised. Tough restrictions, along with poor testing-tracing-treating infrastructure and inadequate social safety programs pushed many Filipinos into poverty.

Unemployment rates were the highest they have been since 2005 during the first quarter of 2020. In the Philippines, the link between poverty and the pandemic is clear. The pandemic has exacerbated existing healthcare inequalities. The imbalance between educated workers versus those who earn daily wages has also worsened due to the pandemic.

India

Like the Philippines, India is suffering an economic recession due to the pandemic. Early in the pandemic, India successfully controlled its impact. Unfortunately, questionable management strategies by the country’s leadership derailed these measures. Despite reducing restrictions and opening industries, India’s economic system remains damaged. The people of India will feel the economic impact for decades to come.

The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) conducted a survey on the unemployment rate in rural India. They found the rate declined from 9.5% in pre-pandemic levels to 7.65% in October 2021. This drop in unemployment primarily affected daily wage earners. Many had to migrate back to their home states once the industries and factories they worked in closed. This national disaster caught the attention of the international community.

Poor social safety nets and policies worsen this unemployment crisis. The informal work sector bore much of the impact of the pandemic. Informal work refers to unregulated labour with little to no job security. Women and children make up the bulk of this labour force. This sector suffers from extensive exploitation, due to a lack of insurance and state economic support. Furthermore, children are taking over adult responsibilities as working family members fall ill. This leads to the beginning of a poverty trap.

The United Kingdom

In the UK, the furlough scheme protected millions of jobs during the pandemic. As of May 2021, close to nine million people benefited from the program. The scheme initially paid 80% of wages for people who could no longer work, gradually lowering to 60% in August and September, with employers contributing 20%. In July, the number had decreased to 1.6 million people. It is undeniable that the scheme has helped save millions of jobs. Early estimates suggested that one in ten people would lose their jobs. As of September 2021, the unemployment rate is less than one in twenty.

The United States

In the US, the government paid $600 a week to anyone that qualified for unemployment benefits during the pandemic. This lifeline ended up changing the economic equation. For many people, such a payment was more than they were earning doing the jobs they lost. At one point, this money was fuelling the economy, with people who had previously earned less spending more, while those with jobs had decreased their spending.

Federal pandemic-era policies ended in September this year, leaving 8.8 million Americans completely without benefits. A further three million have seen their aid reduced to $300 a week. Businesses are hoping the lapse in federal unemployment benefits will bring a surge in job applications. Despite there being many openings, there remains a lag in employment throughout the country. Economists believe that this could be due to a fear of being infected by the virus, as well as a lack of affordable childcare.

How is child poverty worsened by the coronavirus pandemic?

From a strictly medical point of view, children are not a risk category as far as COVID-19 is concerned. However, they are still significantly impacted by the ongoing pandemic. School closures may prevent virus transmission, but the impact on schooling is detrimental. This is particularly true for children living in poverty. Although online learning continues, this intensifies existing disparities. Children from low-income homes will struggle to continue their education, due to poor access to technology or insecure housing circumstances. A further concern is food insecurity. For many of these children, school is the only place they get a nutritious meal.

Girls in developing countries also face the risk of early pregnancies. In the aftermath of the Ebola pandemic, Sierra Leone experienced a pronounced increase in teenage pregnancies. This came as a result of school closures and the loss of adult carers, which forced children to resort to new ways to finding food. Furthermore, the loss of access to contraceptives and an increased exposure to gender-based violence also played a part.

Global poverty: long-term impacts of the Covid19 pandemic.

The UN goal to eradicate extreme poverty by 2030 looks highly unlikely given the pandemic and ensuing global crisis. Plummeting economic growth and vast unemployment is continuing to compound existing inequalities. People living in countries with a large informal sector are at even greater risk. Although all sectors have been greatly affected, tourism and manufacturing stand out, due to the employment they provide for low skilled workers in low income and middle-income countries.

The World Bank has estimated that school closures will cause seven million students to drop out. This will subsequently decrease their earning capacity and increase their likelihood of living in poverty. Such disadvantage invariably leads to greater exposure to COVID-19 and its economic impacts, effectively perpetuating the cycle of poverty and inequality.

Future pandemics: how we can do better

As many as 75% of emerging diseases are zoonotic, meaning they are caused by germs carried by animals. Our effect on climate change, encroachment on wildlife and our travel habits help spread these diseases. This is further exacerbated by urbanisation and overpopulation. In other words, these diseases are becoming more harmful to us a result of our own actions.

These dynamics mean that facing another pandemic sometime in the future is inevitable. To avoid similarly devastating consequences, there must be some changes in how these outbreaks are handled.

Better warning systems

Outbreaks get harder to contain once they’ve expanded beyond a certain area. In 1952, the World Health Organisation set up the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System as an early warning system for flu outbreaks. While unknown pathogens are more difficult to keep track of, improvements in genome-sequencing techniques are making open-ended searches possible.

Better data

At the beginning of 2020, epidemiologists were working off official reports, newspaper articles and social media posts. Access to better data could have helped them determine more quickly that the virus spread through the air, and that it could be transmitted by people without symptoms. Data driven technology will help illuminate the complexities of the disease and the necessary distribution of care in the future.

Better communication

Reluctance to communicate feelings of uncertainty and complex situations resulted in confusion surrounding COVID-19. For example, the use of face masks was initially advised against in certain countries, before the advice was later reversed. This lack of coherent messaging has divided the public in some countries. In the future, attention needs to be given to the spread of misinformation. The public can decipher messages of uncertainty, but contradictory messages will lead to a lack of unity.

Prototype vaccines

Although drug companies developed the COVID-19 vaccines in record time the funding of early-stage work would speed up this process in future. Furthermore, governments should waive intellectual property rights on vaccines during a pandemic to ensure supply in all countries.

Better health care for all

Efforts to connect everyone to a health care system need to be increased. Pandemics exacerbate health disparities, meaning that people from low-income communities’ experience disproportionate infections, hospitalisations, and death.

Want to help?

If you’d like to support the COVID-19 appeal, UNICEF is on the ground in countries and communities that desperately need the most help right now. Your generous donation can help save lives.

Join THRIVE in the pursuit of global shared value creation and collective collaborative peaceful partnerships for people, planet, profit with purpose and prosperity.