Did you know that Canada hosts 25% of the world’s remaining old-growth forests? This number is significantly more than any other country in the world. Yet, a report from the British Columbia government noted that 74% of these forests had been logged.

These pieces of land are important for many reasons. The ability to slow down climate change is one of their most important.

What are old-growth forests?

Old-growth forests are also known as primary forests. They account for major carbon stores on the planet, and provide habitats for large amounts of biodiversity. This includes rare and endemic species, such as, the Northern Spotted Owl, and Southern Mountain Caribou.

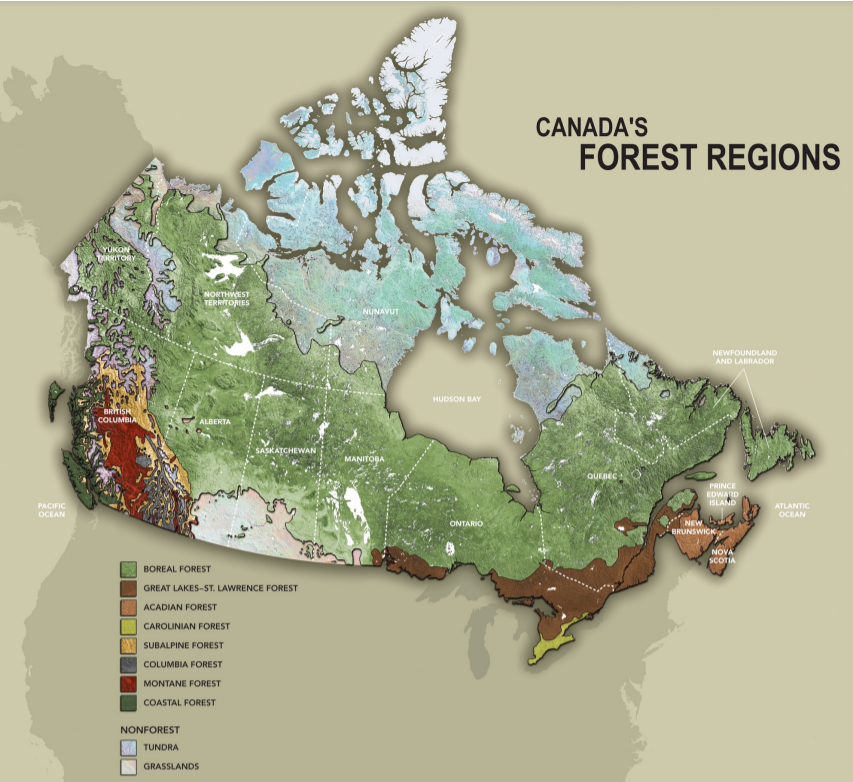

All in all, defining the old-growth forests of Canada is a very difficult task. The variety of ecosystems across the country makes it complex. As does the many species of trees within each forest region. Each forest ecosystem varies in dominant species composition, productivity, and site productivity.

These are the characteristics defining old-growth forests:

- Age

- Structure

- Diversity

- Snags or standing dead biomass

- Tree size

The Department of Natural Resources in Minnesota identifies old-growth forests with two criteria. First, they are forests that develop over long periods of time. And second, they have not been affected by disastrous events. The department also defines a variation of old-growth forests depending on the most dominant tree in the forest.

However, there is another accepted definition from Nova Scotia Nature Trust. It identifies old-growth forests as that which consist of primarily longer-lived species.

Why are they important?

Old-growth forests support many ecosystem services from ecological, economic, cultural, recreational, to spiritual services. Specifically, from an ecological perspective, the benefits they bring are enormous. They include:

1. Biodiversity

Ecologically, old-growth forests provide various habitats for rare and endangered species. They also support greater species diversity than less mature forests. Evidently, the vast and varying ecosystem allows for incredible biodiversity.

2. Carbon sink

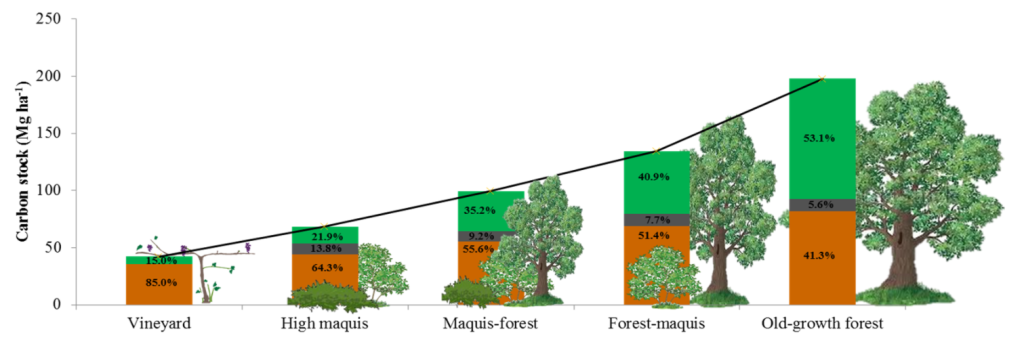

In addition to biodiversity, there are many more crucial ecological functions of an old-growth forest. One being that old-growth forests are global carbon dioxide sinks.

According to a study from the 1960s, international treaties do not protect old-growth forests around the world. The Kyoto Protocol did not identify old-growth forests as national “carbon budgets”. The study stated that forests over 150 years old emit just as much carbon as they absorb. In other words, old-growth forests are carbon neutral. However, more recent research disproves this long-standing theory.

In fact, the older a the tree is, the more carbon the tree is able to sequester. Old-growth forests can hold 2.4 tonnes of carbon per hectare every year. As such, these forests can slow climate change solely on their ability to sequester carbon.

3. Water filtration and storage

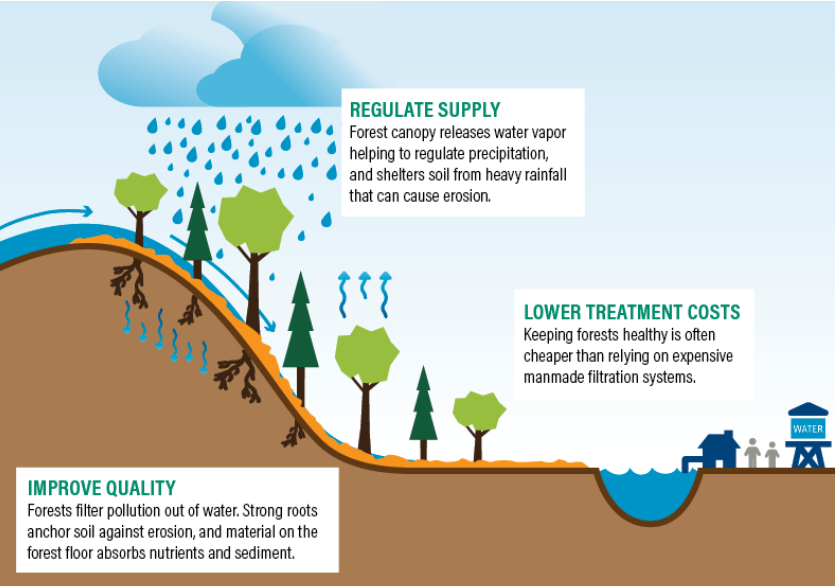

Old-growth forests provide increased groundwater and surface water supply. In the U.S., forests supply a natural filtration and storage system. This system accounts for just under two-thirds of the country’s water supply. Because of similar climates, Canada can assume a similar yield.

In addition, healthy forests are able to keep pollutants away from water bodies. Strong roots anchor soil against erosion. While the material on the forest floor absorbs nutrients and sediments. Together, they prevent pollutants from traveling into waterways. Although this property is not exclusive to old-growth forests, it is still an important ecological service to note.

4. Flood prevention

They reduce flood risk in the case of storms. The amount of water a forest absorbs depends on various characteristics. This includes:

- forest cover area,

- length of vegetation growing season,

- tree composition,

- tree density,

- the age

- and the number of layers of vegetation cover.

In an old-growth forest, these characteristics are abundant. Therefore, it allows for maximum water retention.

Water retention from forests affects the quantity, and the timing, of water delivered to streams and groundwater. Forests are capable of controlling the timing and quantity of water. They do this by increasing and maintaining infiltration. They can even control the storage capacity of the soil. In short, forests absorb excess rainwater, which prevents run-offs, and flooding. They also mitigate drought by releasing water in dry seasons.

Negative effects of logging old-growth forests

We’ve discussed the importance of old-growth forests from an ecological perspective. Now, let’s discuss what happens when old-growth forests face disturbances caused by humans. The main one is logging. Other anthropogenic disturbances include pre-settlement native fires, climate change, and pollution.

Defining acceptable levels of disturbances is difficult. There are no criteria in place that demonstrates an acceptable amount of disturbances.

Above all, the main negative effect of logging an old-growth forest is the potential increase of carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere.

According to researchers from Curtin University, younger and newer forests that replace old-growth forests have lower biomass. And hence, a lower ability to store carbon. Consequently, higher levels of carbon are left in the atmosphere. Old-growth forests are much larger and have larger below-ground carbon pools. Thus, these forests have the ability to retain more carbon than any other kind of forest.

Old-growth forests accumulate carbon for centuries and therefore contain large quantities of it. When these forests are disturbed, much of the carbon stored will transfer back into the atmosphere.

In terms of water retention and filtration, a post-harvested forest will produce water. But, this is short-lived. Because, as the forest re-grows, the water supply declines over time. In addition, water quality is reduced throughout regrowth. When individuals or companies disturb and degrade forests, sediment flows into streams and pollutes water. Deforestation weakens the process of water retention, leading to irregular rainfall patterns, and even drought and flooding.

An unfortunate example of flooding has occurred surrounding the recently logged old-growth forest on Indigenous Patcheedaht and Detidaht territory located on Vancouver Island in Canada.

How to protect old-growth forests

Protecting the old-growth forests of Canada is a very important goal in order to slow climate change, and prevent it from increasing at a rapid rate. There are many other ways to decarbonise, including moving towards renewable energy sources. But, old-growth forests still provide more than enough evidence to mitigate climate change.

Scientists state that reforestation, and better forest management, can provide 18% of climate change mitigation through to 2030.

Still, there are over 30 ways to support old-growth forests. In Canada, 80% of forests are under provincial jurisdiction. Use your voice to lobby for conservation. The old-growth forests of Canada are not just ecological gold. They are our legacy for future generations.

The THRIVE Project plants trees as part of its mission. It is said that planting a trillion trees can dramatically slow down, or even stop, climate change. Maybe, one day, these trees will grow into old-growth forests. Let’s work together to make this a reality.