The recent Netflix series, Tiger King, drew public attention to the breeding, captivity and trade of big cats in the US. However, the appalling conditions in which animals lived became a major concern for many viewers.

According to NGOs, there are more tigers in captivity in the US than there are tigers in the wild globally. Estimates are that America has more than 5,000 tigers either in zoos or in legal and non-legal private facilities.

What effect is trade in exotic animals having on individual species? And how is private ownership affecting animal populations around the world?

In this article we look at the animal trade and the ways that authorities are trying to protect big cats from exploitation.

What is the Big Cat Trade?

The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of the Nature) forecasts the wild Panthera tigris population to be fewer than 4,000 individuals. This puts the tiger species in the ‘endangered’ category.

Tiger breeding is permitted for purposes of conservation, according to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). America has been a signatory to this treaty since 1974. The treaty bans or strictly regulates the trade of ‘species under threat’. However, many US bred felids are ‘crossbreeds’, or ‘generic’ variants. They are, therefore, not considered ‘at risk’.

Moreover, the Endangered Species Act of 1973, does not cover many of America’s exotic pets. This Act only applies to animals taken from the wild. Most of the big cats in the US are born in captivity – in facilities like those featured in Tiger King.

“The vast majority of tigers in the US come from the irresponsible captive breeding to supply the cub petting industry…Tigers are smuggled in, but this is mostly a US-born issue.”

– Ben Callison, a former animal sanctuary director and animal welfare activist, to BBC

Interconnected markets

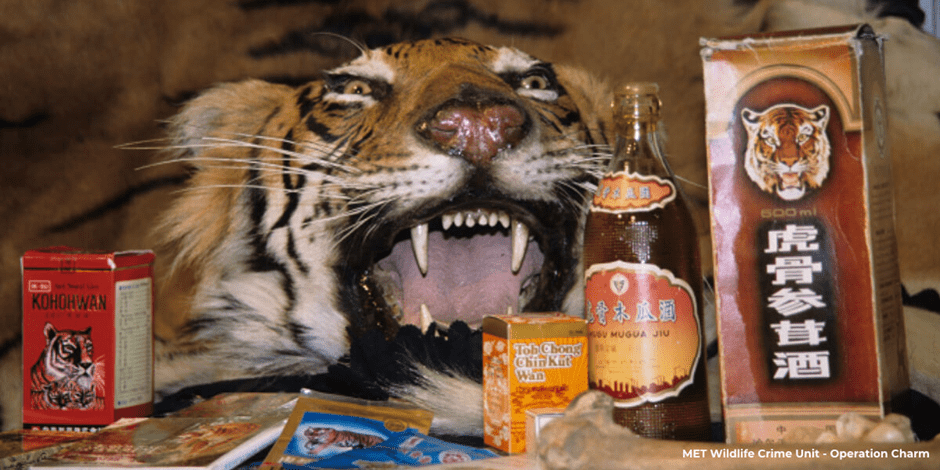

Despite the national demand for exotic felids as pets, when breeders cannot sell cubs, animals end up destined for a life behind bars. Smuggling networks sell and re-sell big cats. Also, there is a multi-billion dollar criminal industry that supplies products for the luxury market in medicinal and decorative animal-based products. Experts believe that farmed tigers in Asia and America are supplying the following markets :

- Roadside zoos and circuses;

- Skin rugs and fur clothing;

- Production of traditional medicines made with animal parts;

- Manufacturing of tiger bone wine – an exotic wine that can cost hundreds of dollars for a single bottle.

The smuggling of big Cats and tiger-based products

It is the illegal trade that hampers efforts to protect fauna and flora. The wildlife smuggling web operates through avenues similar to those used by traffickers. These are global networks trading in drugs, arms, organs, and people. In addition, evidence indicates that there are links to terrorist organisations.

The US imported more than 170 lions and tigers between 2014 and 2018. Zoos, circuses and personal collections are the most common destinations for big cats. The origin of these felids is usually Russia or South Africa.

However, in the trade of tiger-based products, the US buys mostly from China, Vietnam, Thailand, and Laos. These are usually from tiger farms since wild Panthera tigris are virtually extinct in those four countries. Corrupt officials allow the farms access to international trafficking routes.

Who are the Customers in the Big Cat market?

One category of big cat buyer includes breeders and zookeepers. When only a few weeks old young tiger cubs will be removed from their mother. This allows for near constant breeding. Then, ‘exotic animal’ farms will charge visitors to have wildlife experiences which includes petting tiger cubs.

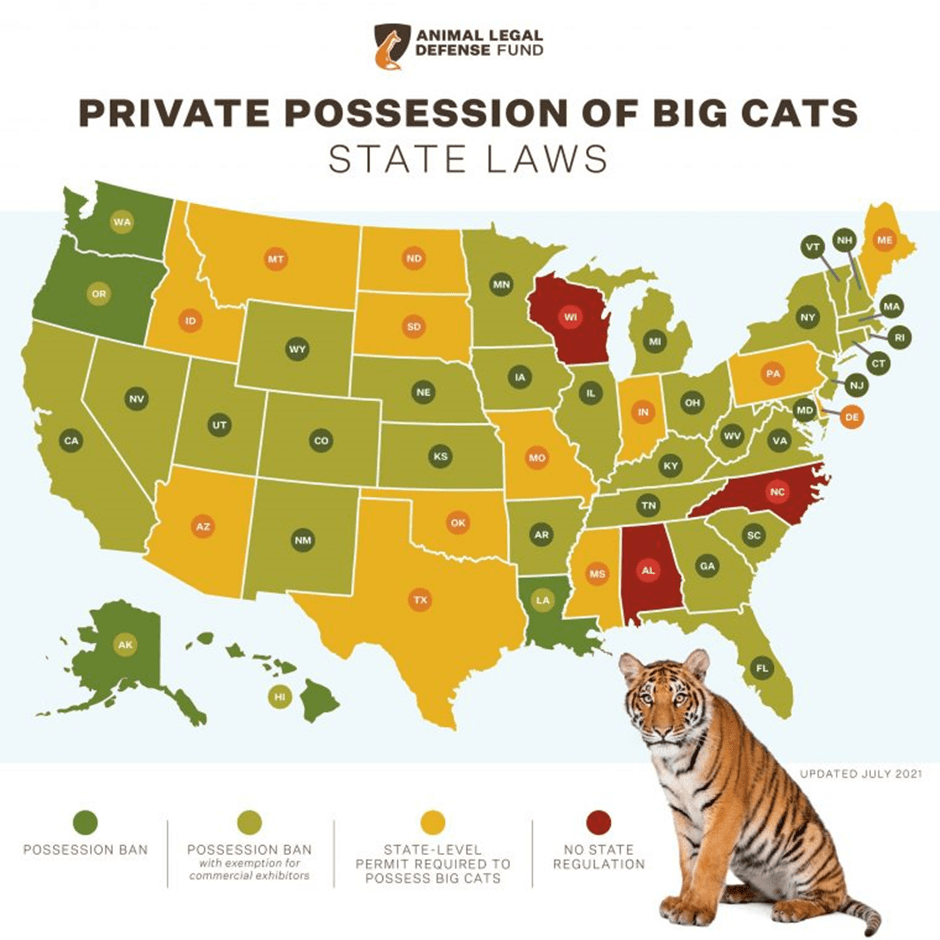

Another customer for big cats are those who want to own exotic animals as pets. Currently, many Americans are allowed to buy and own wild felids like lions, tigers and cheetahs. In 13 states the process to own a pet tiger is surprisingly simple. It only requires a USDA conservation label form and a US$30 license. In fact, it’s astounding just how much easier it is to own a tiger than it is to own a ‘dangerous’ dog in states like Texas. Worse, in Alabama, North Carolina and Wisconsin, there are no legal requirements or prohibitions on people buying pet tigers. This allows virtually anyone to own, breed and sell wild felids.

“At the heart of this surprising tiger turnout is the very American notion of a God-given right to do one’s own thing, including owning a pet – no matter how exotic – being an individual liberty that the state should not mess with”.

– BBC

Finally, there are those buyers looking for animal-based products. Medicinal goods and luxury items made with parts of big cats are expensive. Tiger bone wine, for example, is a highly popular treatment made from tiger bones soaked in rice wine. Chinese and Vietnamese consumers will pay good money for it. Nevertheless, the US is also a key market for teeth, claws and skin pieces.

Among all the tiger parts that enter the US, 81.8% of seized items were medicinal products. San Francisco, Dallas, and Atlanta are entry hotspots for illegal tiger imports originating mainly from China and Vietnam.

The Cost of Trading Big Cats

Whilst tigers are the most popular felids, lions and cougars are also commonly traded. Breeding and trade in the US also extends to leopards, jaguars, clouded leopards, and lion-tiger hybrids.

Lions and tigers can produce around four to six cubs per year. Young cubs would usually stay with their mothers until around 2 years of age in the wild. Here, the cubs are separated from the mother in a matter of weeks to be used in petting cages. Then, in just eight to ten weeks, these adorable miniatures grow into adults predators. When they are too big for petting, they are no longer required by the facility.

The main character in Tiger King, Joe Exotic, explains that there is no real market for an adult tiger in the US. However, Panthera tigris and the Panthera leo can live up to 25 and 30 years of age. In other words, many animals end up spending the rest of their adult lives caged and miserable.

Captivity Issues

Captive big cats are often locked up in small cages. They are deprived of their natural environment and instinctive behaviours. A lack of activity, proper feeding and freedom imposes a massive health burden. They are often frustrated, anxious, and bored. Many suffer from a madness called zoochosis, which is evident in behaviours like pacing, twisting, rolling the neck unnaturally, rocking, swaying, or even self-mutilation. Furthermore, cubs can also experience health deterioration due to the frequent contact they have with tourists. This proximity can cause physical distress, and weaken the immune system, leaving the animals prone to infection.

In addition, captive tigers can also be a serious threat to public safety. Improper care and supervision can create unsafe interactions. In fact, there have been more than 300 incidents involving big cats in the US since 1990, with at least four children losing their lives.

Also, captive animals in unregulated breeding facilities and roadside zoos have very mixed gene pools. They are genetically different from those living freely in nature. Felids in captivity cohabitate with animals from very different areas in the world. This mixing would rarely happen in the wild. Breeders generate subspecies that could devastate original populations if released back into the wild. Unfortunately, crossbreeding means that many of these animals must be ruled out of conservation breeding projects.

Supply and Demand for Big Cats

Finally, since authorities do not adequately monitor many facilities, tigers have become easy targets for illegal trafficking of wildlife specimens and products. Increased trade in these products increases the threat to wild populations by stimulating demand for them. The greater the demand, the greater the risk for all big cats, including those in nature.

The claim for action

The popularity of Tiger King has raised concerns around the conditions, safety and ethics of tiger breeding facilities. Fortunately, this generated great momentum for government to act.

The US House of Representatives passed federal legislation to regulate the possession and exhibition of big cats in December, 2020. Unfortunately, the Senate did not take a vote on the legislation in time, so the bill had to be withdrawn.

However, the Act is back with the Senate and, if passed, it will finally prohibit the private ownership of big cats in the US. Also, it will make it illegal for exhibitors to allow direct contact between the public and cubs. That includes the taking of photos, petting, and similar activities.

Do your bit!

Care for animals and respect for living creatures is an important part of a sustainable and humane society. Protecting both flora and fauna, especially endangered species, is a core value.

Biodiversity is at a tipping point, and it is now critical that we take action for future generations. Thus, it is way past time to get the Big Cat Law Public Safety Act passed. You can get involved, support and sponsor the bill by signing the WWF petition online.

THRIVE is a not-for-profit organisation, for-impact social enterprise. Join the discussion this month on Life on Land (SDG 15). Goal 15 promotes natural habitats and ecosystems, as well as seeking an end to the poaching and trafficking of protected species worldwide. Learn more about wildlife protection around the world and how the loss of biodiversity can affect humans from our blogs, podcasts, webinars, and blogs for the latest sustainability news.